The "Red Christmas" Pattern?

Comparing Covert Operations in Nicaragua (1981) and Suriname (1982)

Introduction

The early 1980s marked a period of intensified covert action by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean, guided by the Reagan administration's anti-communist objectives and the evolving framework of Project Democracy. Examining specific operations reveals potential patterns in strategy, timing, and tactics. This article compares two significant operations planned around consecutive Christmas seasons: the documented "Operation Red Christmas" against Nicaragua in 1981 and an alleged, similarly timed plot against Suriname in 1982. By placing these events side-by-side, we can better understand the operational playbook being deployed and Suriname's potential role as an early proving ground.

Section 1: Operation Red Christmas - Nicaragua (December 1981)

The operation targeting Nicaragua's Sandinista government in late 1981 is explicitly known by the codename "Operation Red Christmas." Its existence and key features are documented in contemporary reports (like the Covert Action Information Bulletin, No. 18) and subsequent analyses (including firsthand accounts like Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz's).

Authorization & Timing: Followed a November 1981 Reagan "finding" authorizing $19.5 million for CIA paramilitary operations against Nicaragua. Major attacks commenced around December 21, 1981.

Actors: Orchestrated by the CIA, utilizing proxy forces including Miskitu indigenous fighters led by Steadman Fagoth and ex-Somocista National Guardsmen (Contras), operating from bases in Honduras with training support from US personnel and Argentine military advisors.

Goals: To destabilize the Sandinista government, potentially incite a secessionist movement among the Miskitus along the Honduran border, create a military crisis, and generate anti-Sandinista propaganda (allegedly by placing Miskitu civilians in harm's way).

Methods: Paramilitary assaults on border villages, fear-inducing propaganda broadcasts, manipulation of ethnic grievances, and related sabotage (like the Dec 12 bombing of a Nicaraguan civilian airliner).

Outcome: Failed to spark a major uprising; led the Sandinista government to evacuate border communities for their protection, neutralizing the immediate operational area. The focus then shifted heavily towards a US-backed propaganda campaign alleging Sandinista atrocities against the Miskitus.

As Constantine Menges later detailed, the Sandinista response to the Miskito uprising included the destruction of virtually all 43 Protestant Indian villages along the Atlantic Coast by early 1982, followed by the forced relocation of over 15,000 individuals into interior detention camps and the displacement of an additional 30,000 to Honduras, where they became the nucleus of an armed resistance movement (Menges 1990, 262–263). This created the very conditions U.S. intelligence had anticipated: a militarized refugee corridor on the Honduran-Nicaraguan border, enabling proxy recruitment and propaganda escalation.

Section 2: The Alleged Plot - Suriname (December 1982)

One year later, events in Suriname culminated in a crisis bearing striking resemblances to the Nicaraguan operation. While direct documentary proof of an official "Red Christmas" codename for this alleged plot is currently lacking, the convergence of factors points to a parallel operation.

Context & Timing: By mid-1982, months before the arrival of Ambassador Robert Duemling, a proactive US covert operation was already well underway in Suriname, aimed at the Bouterse regime which had pivoted towards Cuba. Seasoned operatives Richard LaRoche (Chargé d'Affaires), Edward Donovan (Public Affairs Officer/PsyOps specialist), and Lt. Col. Albert Buys (Defense Attaché) – the "Wolf Pack" – were in place, operating with considerable independence. Their early presence is confirmed by official documents like the State Department's Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts directory for 1982.

Authorization & Planning: This occurred within the framework of NSDD-17 (Jan '82, authorizing support for "democratic forces," PsyOps, and military planning against Cuban influence) and coincided precisely with Oliver North's documented terrorism exercises and capability demonstrations in Washington (Fall '82). The highly classified NSDD-61 (Oct 15, '82), ostensibly about command aircraft security, is suspected of providing specific, deniable authorization for the Suriname operation.

Alleged Plan: Based heavily on the controversial testimony of Peter van Haperen and accounts relayed through figures like André Haakmat, the plot allegedly aimed to overthrow Bouterse around Christmas Eve 1982. It purportedly involved ~80 externally trained resistance fighters/mercenaries, an advance team via French Guiana, external intelligence support (French/Dutch claimed by van Haperen), potential US air support C-130s, and a separate assassination team (the uncorroborated, sensational Brabant Killers link claimed by van Haperen, allegedly trained under North's purview via cutouts like Carl Armfelt).

Outcome: The alleged plot was preempted on December 8, 1982, when Bouterse arrested and subsequently executed 15 key opposition figures (journalists, lawyers, union leaders like Cyril Daal – who met frequently with LaRoche, military figures). Bouterse publicly justified the "December Murders" as necessary to stop an imminent CIA-backed coup.

Section 3: Analyzing the Parallels

The similarities between the documented 1981 Nicaragua operation and the alleged 1982 Suriname plot are significant:

Christmas Season Timing: Both operations were planned to culminate during the politically sensitive and potentially disruptive holiday period.

US Sponsorship & Coordination: Both strongly indicate planning and direction originating from US intelligence (CIA) and national security bodies (NSC), authorized at high levels (NSC finding, potential NSDDs).

Use of Proxies: Both relied heavily on non-US personnel directed or supported by the US – indigenous groups/Contras in Nicaragua; mercenaries/exiles/cultivated internal assets (like Daal and allegedly Horb) in Suriname.

Operational Structure: Both appear to have utilized embedded covert operatives (often under diplomatic cover, as in Suriname) and bypassed or sidelined formal diplomatic channels.

Policy Framework: Both fit squarely within the Reagan Doctrine's anti-communist/anti-Soviet/Cuban agenda and demonstrate the implementation of specific strategies outlined in directives like NSDD-17.

Multi-Layered Approach: Both involved more than just paramilitary action, incorporating psychological operations, propaganda, political manipulation, and military contingency planning.

Geopolitical Targets: Both aimed at nascent leftist or aligned regimes in the Caribbean Basin perceived as threats by Washington.

Section 4: The "Red Christmas" Name - A Shared Codename?

The most striking, and perhaps most suggestive, parallel between the 1981 Nicaraguan events and the alleged 1982 Suriname plot is the name "Red Christmas." This specific codename is confirmed for the CIA-linked operation targeting Nicaragua's Miskito Coast in December 1981, documented in contemporary sources and subsequent historical accounts [see: Dunbar Ortiz, Jarquín Note 3].

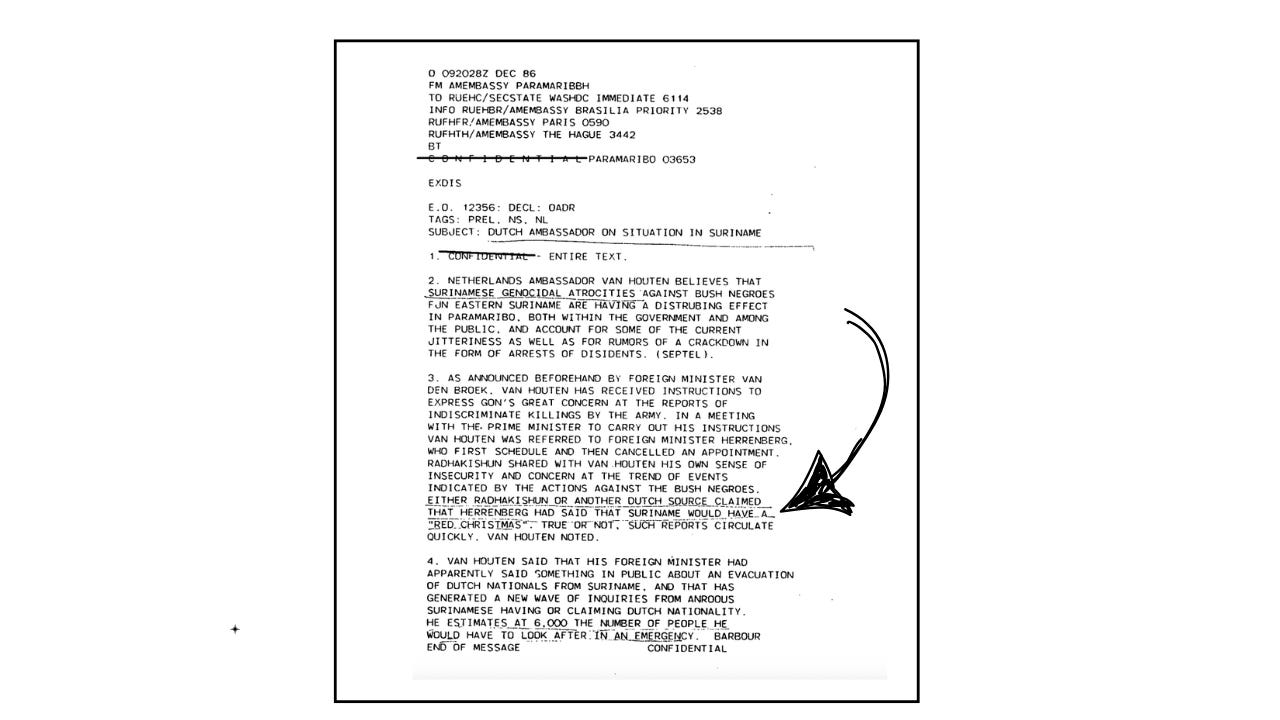

Was this same evocative name officially reused by US planners for the alleged operation targeting Suriname exactly one year later? Direct documentary evidence confirming this remains elusive within currently available public records. The name has become associated with the December 1982 events in Suriname, reportedly used later by Henk Herrenberg to describe the 1986 joint coup planned by the Dutch and United States. It is also conceivable that Bouterse himself, upon learning of a plot timed for the holidays, applied the label based on the well-known Nicaraguan precedent.

Adding another layer of complexity to the name's usage, research by historian Mateo Cayetano Jarquín notes that Sandinista security chief Lenin Cerna later attributed the "Red Christmas" moniker to a different alleged CIA plot targeting Managua's refinery and other infrastructure in early 1982 [see: Jarquín, Note 54]. This suggests the name might have had broader currency during the intense 1981-82 period, potentially applied by different sides to different perceived covert threats timed around the holidays, or perhaps used strategically as a term of art for such operations. Furthermore, speculation raised elsewhere in this research considers if the "Red" might even echo Oliver North's concurrent "Red Cell" counter-terrorism exercises, though this remains purely hypothetical.

Ultimately, while the direct lineage or official application of the "Red Christmas" codename specifically to the alleged 1982 Suriname coup plot requires further confirmation, the powerful resonance of the name combined with the undeniable parallels in timing (Christmas season), context (Cold War anti-leftist drive), methods (covert action, proxies), and alleged US sponsorship makes the comparison historically significant. The pattern itself, whether under an officially shared codename or not, points towards a potentially consistent operational approach during this period.

Conclusion

Examining the documented Nicaraguan "Operation Red Christmas" of 1981 alongside the alleged Suriname plot of 1982 reveals a compelling pattern in early Reagan-era covert action. The Nicaraguan operation provides a clear blueprint – state-sponsored destabilization using proxies, timed for strategic impact, involving multiple layers of intervention. The events in Suriname, orchestrated by seasoned operatives implementing directives like NSDD-17 under the suspected authorization of NSDD-61, fit seamlessly into this pattern.

While the specific details of the alleged Suriname coup plot rely heavily on controversial sources like Peter van Haperen, the wealth of contextual evidence – the policy directives, the personnel deployed, the documented destabilization tactics, the cultivation of assets like Horb, and the timing – makes the existence of such a plot highly plausible. The December Murders appear, in this light, as a brutal but calculated response to a genuine, externally-backed threat.

Together, these "Christmas Plots" underscore Suriname's role not as a geopolitical footnote, but as a critical early laboratory where the aggressive interventionist strategies of Project Democracy were tested and refined, leaving a legacy of violence and unanswered questions.

Hypothesis for Further Research: A Contra-Suriname Through-line?

While this article has focused on the direct parallels between the documented 1981 Nicaraguan "Operation Red Christmas" and the alleged 1982 plot targeting Suriname, subsequent events raise compelling questions about a potential throughline involving Contra forces, particularly Miskito fighters, in persistent efforts to overthrow the Bouterse regime. This section outlines a speculative hypothesis based on available information, inviting further research.

As Menges documents, by 1983 the Miskito refugee population in Honduras exceeded 30,000, and many had direct experience in armed resistance against the Sandinistas, having survived forced relocation, internment, and the destruction of their communities. These displaced populations were already integrated into U.S.-backed Contra efforts and would have represented a highly mobilizable and ideologically aligned force for further regional covert actions (Menges 1990, 262–263).

The Known Points:

Nicaragua '81: The conflict involving Miskito Indians on Nicaragua's Atlantic Coast saw significant violence around the Christmas seasons. The Sandinista government dated the start of the Faggoth-led "'Red Christmas' Indian revolt" to December 1, 1980. Separately, the term "Operation Red Christmas" became associated with CIA-linked Contra/Miskito operations peaking in December 1981, reportedly involving Argentine advisors. These events resulted in the flight of ~13,000 Miskito refugees to Honduran camps by late 1983.

Suriname '86: A documented (via undercover operation) coup plot led by Tommy Lynn Denley explicitly planned to use approximately "400 Miskito Indian contras from Nicaragua," sourced via Honduras and funded through networks linked to Oliver North and Robert Owen. This confirms Miskitos were targeted for recruitment for Suriname operations by these networks later in the decade.

The Potential Bridge (Dr. John McClure, 1983-1984):

John McClure, operating between late 1983 and early 1984, developed detailed invasion plans (Plans A, B, C) for the Surinamese Council for the Liberation. His plan involved sourcing the primary invasion force, estimated at 300-400 fighters, from the M3 Contra faction, a group he had recently affiliated with, led politically by Alvaro Taboada and militarily by "El Gringo".

The Speculative Hypothesis:

Could the M3 fighters Dr. John planned to recruit for Suriname in 1984 have been, or intended to be, largely Miskito Indians, thus representing an earlier iteration of the strategy explicitly planned by Denley in 1986?

Supporting Breadcrumbs & Areas for Investigation:

Recurring Force Size: Both Dr. John's 1984 plan (sourcing from M3) and Denley's 1986 plan (explicitly Miskitos) centered on a force of approximately 400 Nicaraguan Contra fighters. Was this a coincidence, or did both plans tap into the same available pool of manpower?

Available Miskito Pool: The December 1983 amnesty freed ~300 Miskitos imprisoned for resistance activities since late 1980/early 1981. This created a pool of experienced, likely motivated fighters available precisely when Dr. John confirmed M3 could supply troops. Furthermore, the ~13,000 refugees in Honduran camps represented another potential source.

Dr. John's Miskito Awareness: Dr. John was demonstrably aware of Miskito Contra factions and their leaders, such as Brooklyn Rivera and Hugo Spadafora. Did his connections (e.g., to Spadafora) play a role in his M3 recruitment strategy, even if M3's formal leadership was distinct? (Note: The Sandinistas differentiated between Faggoth's excluded faction and Rivera's included faction in the '83 amnesty).

M3's Composition & Needs: M3 needed fighters and operational successes to gain credibility and potential funding from US sources. Miskito groups were experienced fighters potentially seeking resources. Was there an undocumented agreement or plan for M3 to recruit from or partner with Miskito forces for the Suriname operation?

North/Owen Network Overlap: The North/Owen network demonstrably funded Miskito factions and was explicitly linked to sourcing Miskitos for Denley's 1986 plot. Was this network also implicitly or explicitly involved in Dr. John's 1984 planning via his contacts (like the alleged CIA station chief Joseph Fernandez or DIA colonel ) or the M3 leadership, potentially earmarking Miskitos even then?

Continuity Figures: Could figures like George Baker, allegedly involved with both Dr. John ('83/'84) and Denley ('86) , provide evidence of continuity in planning and potentially the specific fighters targeted? Research into Baker's specific role and contacts within different Contra factions could be revealing.

Council for Liberation Records: Do any surviving records or testimonies from the Council for the Liberation regarding the 1984 planning specify the intended ethnicity or origin of the M3 fighters Dr. John was tasked with recruiting?

Conclusion:

While the available documentation on Dr. John's 1984 plan specifies fighters sourced from M3, the context is highly suggestive. His awareness of Miskito groups, the later explicit use of Miskitos in the 1986 Denley plot, the consistent force size (~400), the timely availability of freed Miskito dissidents and refugees, and the potential overlap in funding networks (North/Owen) and coordinating figures (Baker) raises the plausible hypothesis that Miskito Contras were the intended fighting force for Suriname as early as 1984. Establishing this definitively requires further investigation into the specific composition and recruitment plans of M3 during that period and the precise nature of the connections between M3 leaders, Dr. John, Miskito commanders, and US intelligence networks. These "breadcrumbs" suggest a potentially deeper and more consistent strategy of leveraging Contra forces for Suriname operations than is immediately apparent.

Sources Cited

Covert Action Information Bulletin:

Covert Action Information Bulletin, Number 18 (Winter 1983). "Special: The CIA and Religion." Accessed via CIA Records Search Tool (CREST), General CIA Records Collection.

Document Number (FOIA) / ESDN (CREST): CIA-RDP90-00845R000100180004-4

Online Access: https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/document/cia-rdp90-00845r000100180004-4

(Note: This issue contains multiple relevant articles, including "The Miskitu Case" discussing the Nicaraguan operation and the "Destabilization in Suriname" news note).

Dunbar Ortiz Chapter on UN Human Rights Seminar:

Dunbar Ortiz, Roxanne. "The First Ten Years: From Study to Working Group, 1972-1982."

In Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in International Law: Emergence and Application: Book in Honor of Asbjørn Eide at Eighty, edited by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Dalee Sambo Dorough, Gudmundur Alfredsson, Lee Swepston, and Petter Wille.

Publication Series: Gáldu Čála 2/2015.

Publisher/Year: Gáldu Resource Centre for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Kautokeino & Copenhagen), 2015.

(Note: This chapter contains the detailed account of the UN seminar in Managua coinciding with the launch of Nicaragua's "Operation Red Christmas").

Jarquín Article on Nicaraguan "Red Christmas":

Jarquín, Mateo Cayetano. "Red Christmases: the Sandinistas, indigenous rebellion, and the origins of the Nicaraguan civil war, 1981–82." Cold War History 18, no. 1 (2018): 91-107. Published online August 8, 2017.

(Note: This article provides a detailed analysis of the December 1981 conflict between the FSLN and Miskito Indians known as "la Navidad Roja." It examines the competing narratives (FSLN mistake vs. CIA plot), emphasizes the early role of Argentine and Honduran intervention alongside indigenous agency, and discusses the complex usage of the "Red Christmas" name).

Constantine Christopher on Sandinista relocation of Miskito Indians.

Menges, Constantine Christopher. The Twilight Struggle : The Soviet Union v. the United States Today. Washington, D.C. : AEI Press ; Lantham, MD : Distributed by arrangement with National Book Network, 1990. http://archive.org/details/twilightstruggle0000meng.