"You want to go with your dad to visit the bank in the morning?" Mom asked, tucking me into bed as a gecko’s tiny feet scurried across the ceiling.

That evening, Bouterse had come on TV yet again with an announcement that shattered how my view of reality. Our money—everyone's money—was worthless.

It was the week before my eleventh birthday in 1986, and I had just started sixth grade when the civil war broke out. At least seven confirmed rebel attacks had occurred in eastern Suriname, including the capture of the police station on Stoelman's Island on the upper Marowijne, where the rebels seized control of the airstrip. On October 7, 1986, Brunswijk's group took five employees from a palm oil company hostage in the village of Patamakka, in eastern Suriname. According to the news, the “criminal and terrorist gang” caused millions of guilders worth of damage in the village. The group set fire to a post office, police post, the palm oil company's office and warehouse, ten houses, and even an outpatient clinic. They doused everything with diesel oil before lighting the inferno.

Ten days later, the Black Robin Hood and his band of Jungle Commandos hijacked a plane at a jungle resort about 100 miles south of Paramaribo. They released the passengers but forced the pilot and co-pilot to fly to Langatabbetje island in the Marowijne River, where my friend Matt and his family lived. This became Brunswijk's new headquarters. The pilots managed to escape, but the Twin Otter plane remained with the rebels until a ransom of 800,000 Dutch guilders was paid.

This chaos was the handiwork of George Baker and the ANSUS Foundation, who had hired British mercenaries John Richard and Carl Finch (aka Karl Penta) to lead Brunswijk's guerrillas in bombing bridges and seizing control of roads from Albina to Moengo and from Moengo to Paramaribo. The online publication The Velvet Rocket does a great job providing a photographic tour of the journey taken into Suriname by Penta. The mercenaries forced the closure of bauxite mines and shut down the Paramaribo airport on October 20th, leaving us with no way out of the country. None of us knew how long it would be until they reached the capital.

Even before the rebel attacks, the government exported most of the country's national resources. You could hardly buy even sugar or coffee. But after the attacks, supply lines broke, and many shopkeepers in Paramaribo shuttered their stores altogether. Shelves in the markets went bare. Mom waited for hours in line for bread—the same for milk, which she carried home in warm, hermetically sealed plastic sacks, the liquid sloshing with each step.

There was an understood family rule in Suriname: if you see a line, pull the car over, and someone hop out and join. We'd have no idea what we were waiting for; you could end up with chocolate or cigarettes. But even Bouterse couldn't declare those worthless, and at least we'd have something to trade!

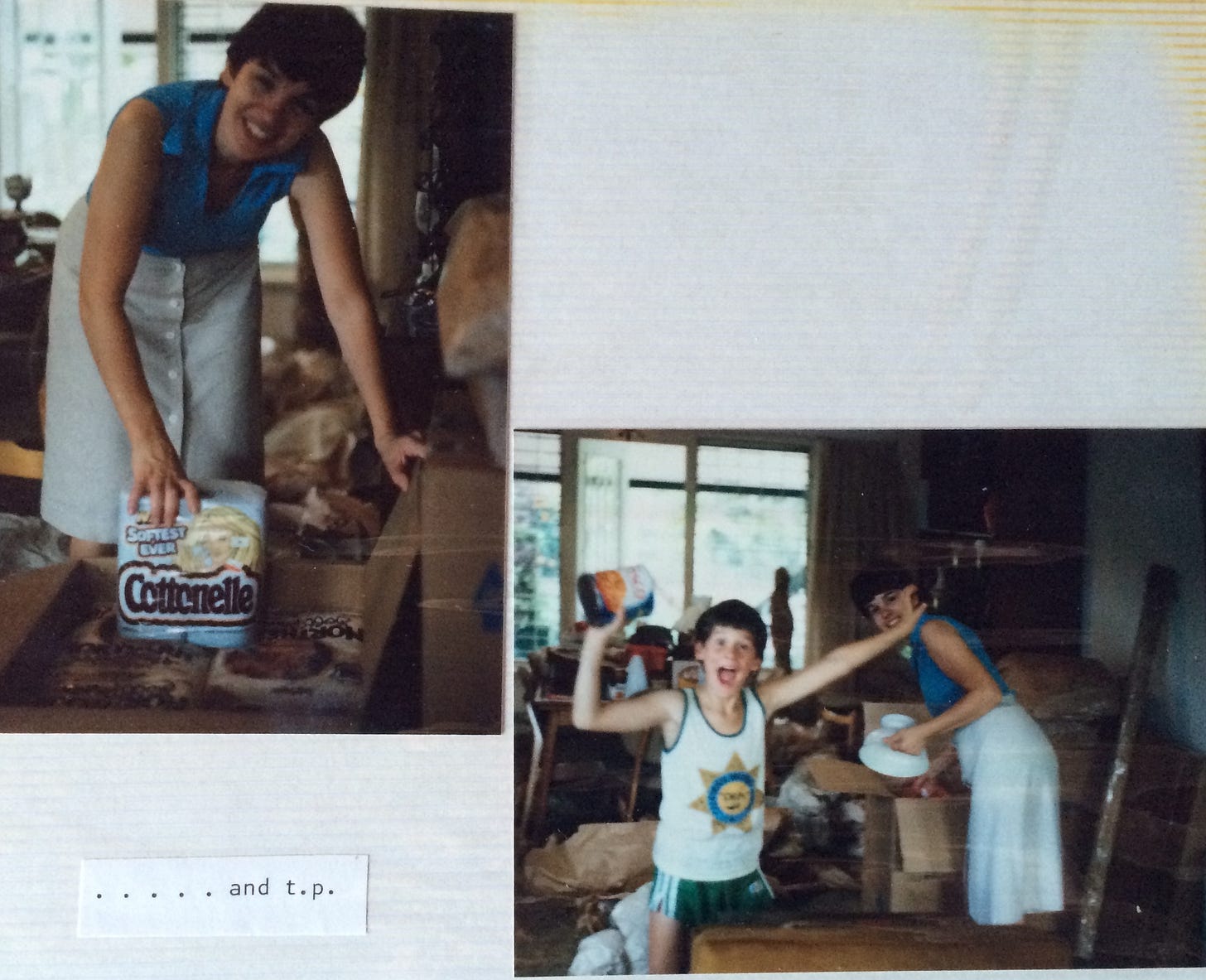

When requesting support from churches back home, Mom and Dad joked in our family newsletters that the country was "wiped out" of basic necessities like toilet paper. There's a picture of me unloading a packing crate, arms raised like I'd won the Olympics, with a vat of Crisco and a full-toothed smile fit for Christmas morning.

After our first year as missionaries, our support dropped to 60% of what was required—likely because we'd hurriedly raised money from churches that didn't know our family very well. ALCOA's hiring incentives, like the maid and the gardener, also dried up. Compounding matters was the skyrocketing inflation. Central Bank President Henk Goedschalk pumped more guilders into the economy in a vain attempt to keep things afloat.

Fortunately, my parents were resourceful, and we learned other ways of getting what we needed. Much later, I learned it had a fancy name called arbitrage. But back then, we just called it the black market—something Wycliffe explicitly forbade.

The black market loved two things: American dollars and technology. The country was full of hosselaars, or smugglers, who would buy items in Surinamese guilders and then trade them in French Guiana at significant profits, where the exchange rate was one guilder to three francs. Smugglers were aided by Brunswijk's Jungle Commandos, who snuck these products across the border via small boats called korjaals on the Marowijne River, along the border of Suriname. Wycliffe exchanged American dollars at the going rate—one dollar for 1.7 guilders (now 1:32). But on the black market, Dad knew a Chinese guy who owned a 1980s Surinamese version of a Walmart, who was desperate for dollars. He paid eight guilders for one American dollar, while others paid up to thirteen to one. This allowed us to make up the difference in lost income with a side hustle of selling things, like our used VCR, and shipping in a new one.

Bouterse's newly announced money initiative hoped to address some of these financial concerns, by drying up the black market money, and rendering worthless all the ransom money and bank robbery loot Brunswijk had stashed.

The next day, Dad and I arrived at Handels Krediet en Industrie bank (the locals called it Hankrin) in the center of Paramaribo with over ten thousand guilders. Some of the money was ours, but the bulk of it belonged to the school. It was the most cash he had ever carried in his life.

Monday was slated for large bills—100 and 500 guilders or larger. Tuesday, you could swap 10s and 20s, followed by 1s and 5s on Wednesday. Caps of $2,500 were implemented, with checks issued for larger amounts once funds were verified. Lines strung out the door and snaked around the block. Policemen and soldiers worked to maintain order as the entire town had shut down and shown up, clutching millions of guilders of soon-to-be worthless paper representing their life's work. We stood all day in the relentless sun while Dad turned as red as a Suriname apple.

Mr. Van Dunslager, who'd let me stay with him while my turtle hatched, had a wife who worked with Dad at the American Cooperative School. He was a pilot for SLM Airways (which Bouterse now owned). Bouterse tasked him with flying an empty plane to London to pick up millions in stacks of newly minted Surinamese currency.

By now, the Jungle Commandos had gotten wind of Bouterse's plans, and through their network of sympathizers and accomplices in Holland, the U.S., and both Guianas, they hatched a plan of their own. Over the weekend, new classified ads appeared in the Netherlands, offering to buy soon-to-be-worthless guilders from ex-pats who'd left the country a decade prior for pennies on the dollar.

Ronnie's rebels chartered planes and flew them into Guyana. From there, they snuck through the jungle and drove suitcases full of cash the rest of the way into Paramaribo, where Dad and I waited in line with the rest of the country. Skipping the lines, they went straight to the back of the bank, where accomplices let them in and allowed them to make large exchanges not available to your ordinary Surinamer. Or at least this is the story I heard from my father.

As this spectacle unfolded, my brain struggled to grasp what was going on. Our pastors preached that primarily dust and moths corrupt your earthly treasures, but never did they mention inflation or autocrats. The bank scene descended into organized chaos—as cries of anger and frustration echoed off the walls. All around me, grown men and women’s faces contorted in anguish as they clutched useless stacks of currency. Their life's work, rendered worthless by the stroke of a dictator's pen.

Yet, somehow the real things held value—the surprise cigarettes we'd waited hours for, the chocolates that brought simple pleasures. While Bouterse could declare these people’s life’s labor void, no decree could stamp out the joy of candy melting on your tongue or an old man’s calming ritual of a smoke's deep exhale. Those were real because they fulfilled human needs no politician could erase.

In that moment, my belief in money dissipated. I realized it was just an idea, humble paper made precious by the mutual faith that human effort, distilled to numbers on a slip, could be traded for what we truly required to survive. But Bouterse had broken that deal. As despair rippled through the crowd, it dawned on me that money was a cynical illusion—one that powerful politicians and backdoor bankers could remold on a whim to suit their greed and settle their scores.

I LOVED this one. It combined the action with the personal narrative, where I started to see where you and your family stood in all this.

I kept wondering: what were you feeling during this time? And what were your parents feeling? If I was stuck in a foreign country under seige and the airports were shut down, I would be freaking the f*ck out. Can you share more about that?

Also super interesting to know that you had that insight about money at that age, in that moment.