The Secret War for Suriname: Part I

The Coup, the Doomsday Plane, and the Blueprint for Shadow War

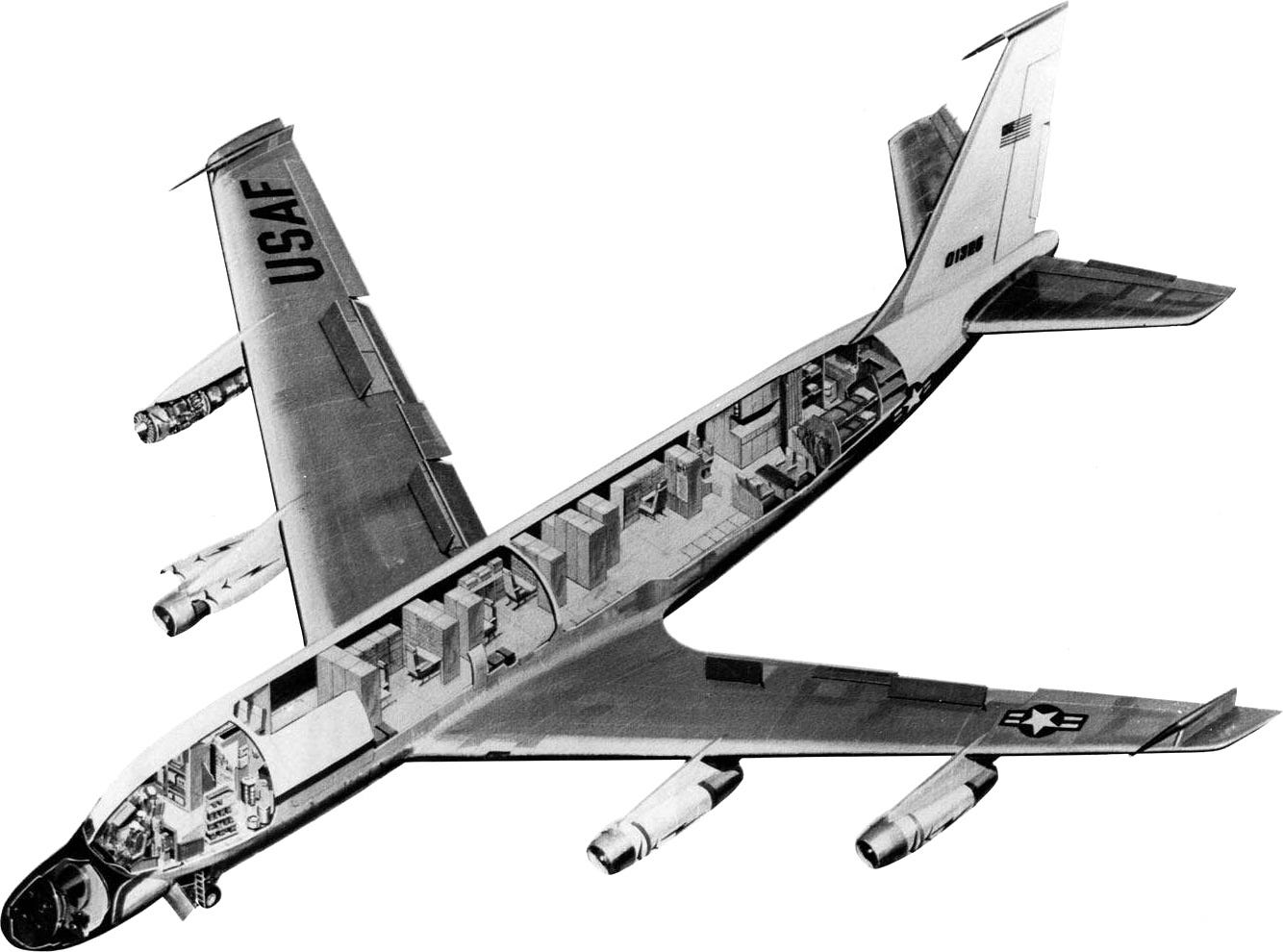

That photograph, taken moments after my family landed in Suriname in 1985, captures us on a seemingly innocuous stretch of tarmac. I was ten. What I couldn't comprehend then was that this runway at Zanderij International Airport was a scar from a recent, deep tremor in the Cold War. Five years prior, two high-tech U.S. Air Force EC-135s—their "Snoopy Noses" packed with sensitive equipment—were marooned here during a sudden military coup, an incident that would send shockwaves through America's defense establishment.

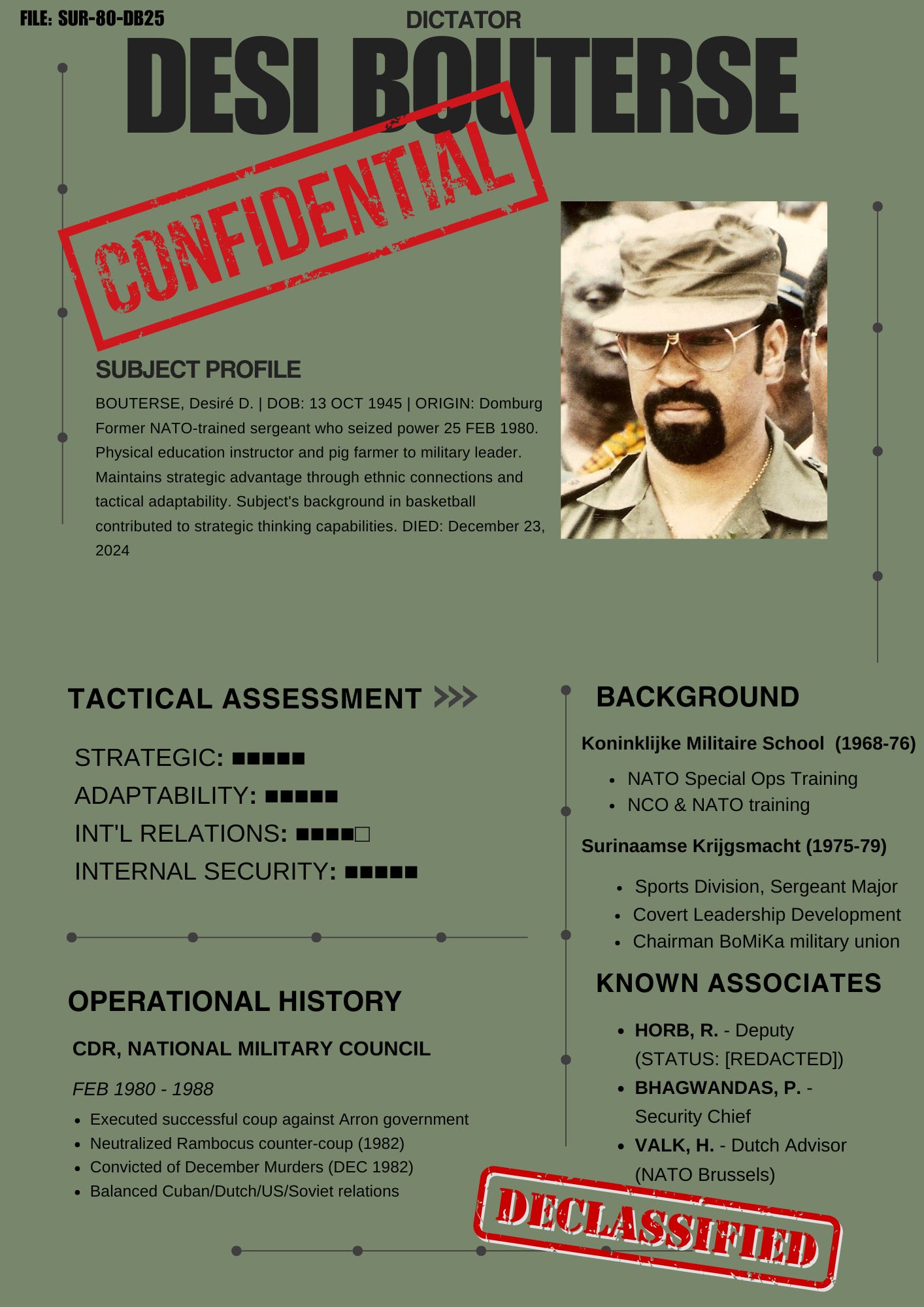

As I've shared before, my childhood as a missionary kid from Indiana was spent not just near power, but literally next door to it—next door to a man who would use that power to terrify, silence, and kill. Desiré Delano Bouterse (BOU-ter-suh) wasn't a distant historical figure; he was the dictator sharing our back fence. "Desi," or "Bouta," the neighbors whispered. From my clubhouse roof, I’d train my telescope on his pet panther, watch teenagers patrol his compound with UZIs. Whispers of torture were the chilling soundtrack to a surreal upbringing.

Our presence in this geopolitical tinderbox was no accident. The 1980 Sergeants' Coup accelerated a brain drain that had begun before Suriname's 1975 independence. With skilled expatriates fleeing ALCOA Aluminum’s vital bauxite operations, the company partnered with SIL (Summer Institute of Linguistics), Wycliffe Bible Translators' foreign arm. My father, spotting a magazine ad weeks before seminary graduation, was recruited as a school administrator into this vacuum. Our prominent house, nestled beside Bouterse and his Finance Minister, complete with staff, was part of a calculated corporate and diplomatic effort to maintain Western presence in a resource-rich nation Washington deemed too valuable to lose. Suriname's bauxite was more than an economic asset; it was a strategic imperative, intertwining commerce and national security, elevating this small nation's importance far beyond its size.

But in February 1980, five years before our arrival, "Desi" wasn't yet the feared President and Commander of the Armed Forces. He was a recent Sergeant Major, a former basketball star and chicken farmer who, with fifteen disgruntled NCOs armed with stolen shotguns and air rifles, launched an improbable coup that would force a terrifying reappraisal of American defense strategy. The incident involving those stranded U.S. military aircraft wasn't merely an embarrassing diplomatic hiccup; it exposed a critical vulnerability in America's technical infrastructure that rippled all the way to the White House.

My childhood memories of Bouterse's regime offered only glimpses of a much larger strategic chess game unfolding across the hemisphere. The incident that had happened five years before our arrival—those two stranded military aircraft—represented more than just an awkward diplomatic episode. Those planes were part of a critical technical infrastructure that, when compromised, triggered a fundamental reassessment of American security planning.

Years later, President Reagan would boast, "not one inch of ground has fallen to the communists" during his tenure, listing nations like Grenada, invaded in 1983 using repurposed Suriname invasion plans. On Suriname itself, however, he remained silent. He had to. Under his watch, "Project Democracy"—his covert operations brainchild—had culminated in the December 1982 murders of fifteen prominent Surinamese citizens. And the truth was even darker: Reagan’s administration would end up shielding their killer.

This is the blueprint of how that shadow war began.

The Spark: A Sergeant's Coup and Stranded Strategic Assets

February 25, 1980. Suriname, barely five years independent from the Netherlands, imploded. Economic ruin, rampant corruption, and seething military discontent ignited the Sergeants' Coup. Sixteen NCOs, led by the 34-year-old Bouterse, overthrew Prime Minister Henck Arron, ostensibly to salvage their nation's promise.

Few in America understood Suriname's quiet role as a vital node in the U.S. military’s global logistics and intelligence web. Zanderij International Airport wasn't just another airstrip; it was a crucial transit hub for U.S. South Atlantic flights, a legacy of WWII agreements forged when the Netherlands fell to Nazi Germany and America moved to protect Suriname's strategic bauxite. The U.S. Air Force Mobility Command depended on Zanderij for refueling. More critically, the airport provided a discreet base for sophisticated intelligence gathering, offering isolation from Soviet espionage, a (hitherto) stable political climate, and prime geographic positioning. Until February 25, 1980.

"Every time NASA launched a satellite, they would send down two Air Force EC-135s... they had to fly out for six hours, orbit, and then return to land in Suriname." – Neul L. Pazdral

The Crisis Unfolds

When Bouterse's men seized power, two U.S. Air Force EC-135N A/RIA aircraft sat exposed on Zanderij’s tarmac. Their 26 American crew members were trapped at their hotel. These were no ordinary planes. They were flying command posts, airborne eyes and ears critical for satellite tracking, telemetry, and integral to America’s nuclear war infrastructure and nascent Continuity of Government (COG) functions. While not primary "Doomsday Planes", (designed to keep the President alive during nuclear attack), these A/RIA were vital cogs in that machine.

These specialized platforms, with their "Droop Snoot" radomes housing seven-foot steerable antennas, were mobile tracking stations, jointly funded by NASA and the DoD at $4.5 million apiece. Their predicament in Suriname didn't just strand expensive hardware; it laid bare a fundamental flaw in America's COG framework. The existing system—bunkers, airborne command posts, secure communication lines—assumed a swift, cataclysmic nuclear exchange, a "spasm war," not a protracted conflict demanding sustained leadership. The Zanderij incident became a brutal catalyst, forcing a seismic shift in U.S. strategic thinking: from preparing for a brief atomic exchange to girding for prolonged nuclear conflict with resilient, functioning governance—a doctrinal revolution later repurposed for covert operations under Reagan.

Deputy Chief of Mission Neul Pazdral recounted Surinamese troops seizing the airport, threatening to shoot if the planes moved. Pazdral negotiated directly with Bouterse, who, possessing NATO training, knew better than to provoke America on day one. The mission was aborted. A dangerous blind spot in U.S. national security had been glaringly exposed.

This vulnerability of Cold War surveillance keystones was a jolt that reverberated through the Carter administration, revealing multiple critical weaknesses:

Intelligence Catastrophe: A total vacuum. Suriname, considered a sleepy backwater, hosted America’s smallest South American embassy, devoid of any CIA presence. Overnight, a vital U.S. hub fell to sixteen NCOs whose allegiances were utterly unknown.

Global Exposure: If two strategic U.S. aircraft could be neutralized by a minor coup, what if a nuclear crisis erupted while top U.S. leadership was airborne or abroad?

The "Federal Arc" Failure: The ring of hardened command bunkers around Washington D.C., an Eisenhower-era construct, was now perilously vulnerable to Soviet targeting. A classified assessment was bleak: "our present system of alternate hardened sites for the Executive Branch are not adequate to withstand a Soviet attack." They were known Soviet targets, inadequately hardened, and critically, offered no solution for getting leadership to them during an attack. The EC-135 debacle vividly showed how even airborne assets could be compromised.

A Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) study conducted in 1979 painted an alarming picture: minutes into a Soviet attack, "all of the major nodes (White House, Crown helo, NMCCS, etc.) of the current C3 system except for SAC's Airborne National Command Post and the Post Attack Command and Control System would be gone."

Translation: the U.S. capacity for nuclear retaliation would be crippled.

(For those interested in a deeper dive, I’ve added additional research on these planes here.)

The Persistent Vulnerability: From Zanderij to Cuban Staging

The February 1980 Zanderij incident had exposed a critical vulnerability that continued to haunt U.S. planners throughout the early Reagan years. What initially appeared to be an isolated diplomatic embarrassment revealed itself as a harbinger of far more serious strategic threats.

As Assistant Secretary Charles Anthony Gillespie Jr. later confirmed, Cuban interest in Suriname's airport wasn't theoretical—it was operational and immediate. "We had intelligence that the Cubans were sniffing around Suriname," Gillespie recalled. The strategic logic was chillingly clear: "The Cubans were in Angola and moving in and out of Angola. One of the problems that the Cubans had was finding way stations on the route to Africa—for refueling and that kind of thing."

Zanderij International Airport, with its long runways and strategic location, represented exactly what Cuban planners needed. "Well, Grenada had been a possibility, but Grenada wasn't ready yet," Gillespie noted. "Suriname had a big airport which was perceived to be very attractive to the Cubans."

The same airfield that had trapped America's EC-135s in 1980 was now potentially becoming a Cuban staging area for African operations by 1982. This wasn't just about protecting American corporate interests or preventing another leftist government in the hemisphere—it was about denying the Soviet Union a critical piece of global logistics infrastructure that could fundamentally alter the balance of power in Africa.

The vulnerability that began with sixteen sergeants and some stolen shotguns had metastasized into a potential Soviet strategic breakthrough. The COG reforms Carter had initiated in response to the EC-135 crisis would soon be weaponized by his successor into something far more aggressive than defensive preparedness.

Beyond Nuclear Jitters: Corporate Assets at Risk

The EC-135 stranding ripped holes in America's nuclear command-and-control fabric. But it also spotlighted another acute vulnerability: the security of massive American corporate investments in Suriname. This nation wasn't just a former Dutch colony; it was a bauxite treasure trove, essential for aluminum production. The Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA), through its Suriname Aluminum Company (Suralco), had operated there since 1916. By 1980, these weren't just facilities; they were strategic U.S. assets. Bauxite and alumina constituted roughly 80% of Suriname's export earnings and 40% of government revenue.

This mineral wealth was strategically vital. Aluminum was indispensable for civilian manufacturing and military hardware—from aircraft to weapons. In the Cold War calculus, secure access to such resources was paramount. U.S. officials, as scholar Paul Kengor noted, deeply feared Soviet "resource denial" strategies.

The Sergeants' Coup demonstrated with terrifying speed how a stable political climate could vaporize. Bouterse's NCOs, seizing power overnight, gained de facto control over resources and infrastructure built by decades of American investment. This trifecta—strategic minerals, significant corporate presence, sudden political implosion—was an alarming cocktail for Washington. It also explains my family’s prominent posting next to Bouterse: we, like other Western expatriates, were unwitting pawns in a corporate-diplomatic strategy to maintain a foothold in a nation too valuable to abandon. This entanglement of corporate and strategic interests was a well-worn path in Latin America—United Fruit in Guatemala, ITT in Chile. Suriname, however, became a bridge from these cruder corporate interventions to the more sophisticated, deniable operations of the 1980s. Nuclear vulnerability and corporate resource protection: these seemingly disparate anxieties converged in Suriname, creating a perfect storm that would soon engulf the incoming Reagan administration.

A Cascade of Crises: America's Unraveling Defenses

The timing of the Zanderij incident could not have been more ominous. Weeks later, on March 14, 1980, the National Military Command Center scrambled during a "Threat Assessment Conference Call": Soviet missiles launched from the Kuriles appeared to be streaking towards North America. Declassified records state "the 'fan' of one of the missile tracks included Alaska, Canada, and the tip of Oregon." Strategic Air Command (SAC) went on high alert; the National Emergency Airborne Command Post (NEACP) "rolled" at 2132 hours.

This missile threat proved a false alarm, but its chilling proximity to the Suriname debacle amplified fears about America's command, control, communications, and intelligence (C3I) systems—the very nervous system of nuclear response. General William Odom, White House military aide, delivered a terrifying assessment: "Our C3I vulnerability is extremely serious. A small Soviet attack on our C3I could make it virtually impossible for the surviving or successor NCA to retaliate for days and weeks, perhaps months." This wasn't a new fear—National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski had warned President Carter in 1977 about the "relative rigidity of the SIOP options." But the Suriname incident transformed abstract anxieties into a concrete, undeniable emergency, demanding urgent reform in what Reagan would soon view as "America's backyard."

Forging the Shield: Carter's COG Revolution

Emergency Preparedness Revolution

While the Carter administration had been incrementally reforming strategic doctrine, the Zanderij incident galvanized unprecedented direct presidential action. Carter, spurred by the EC-135 crisis and the March 1980 missile scare, personally spearheaded an emergency preparedness revolution.

Within four months of Zanderij:

Operation TREETOP (Spring 1980): Carter explicitly requested this program to disperse five potential presidential successors with mobile support teams during strategic crises. Its design: "reduce greatly our vulnerability to a surgical strike against the National Command Authority." TREETOP was radical, abandoning fixed, targetable bunkers for the elusive defense of uncertainty and dispersion. It acknowledged a terrifying new reality: in the age of ICBMs, no bunker was truly safe. Mobility, redundancy, dispersal—these became the new COG watchwords. This mirrored the Air Force's MX missile program, which, as Annie Jacobsen detailed in "Phenomena," planned to shuttle missiles around a vast, classified rail network in Nevada and Utah—"location uncertainty" was the shared principle, making Soviet targeting a nightmarish gamble.1

Exercise NINE LIVES (May 1980): Conducted "at the President's request," this was no routine drill. FEMA Director John Macy reported directly to Carter that it tested an integrated response to "a rapidly deteriorating worldwide situation leading to nuclear war." It deployed real assets, testing everything from helicopter evacuations to SIOP execution from alternative command sites. It was the first "coordinated and concurrent exercise of emergency plans in support of the President and his potential successors" in U.S. history—a watershed moment.

U.S. Army's Intelligence Support Activity (April 1980): A new covert unit emerged, designed to operate outside formal CIA findings or congressional oversight, offering deniable options for precisely the kind of sensitive missions brewing in places like Suriname. (Its birth, aimed at the Iran hostage crisis, coincided with the first alleged coup attempt against Bouterse by Fred Ormskerk, though no direct link is proven.)

Presidential Power Solidified: The Directives

Presidential Directive 58 (PD/NSC-58, June 1980): This was Carter's direct intervention. White House aide William Odom noted Carter's hands-on participation "gave a much needed check of our plans." Signed just four months after Zanderij, PD-58 on "Continuity of Government/C3I" established a Joint Program Office and a White House Steering Group, fundamentally reimagining U.S. government survival during nuclear war. It mandated capabilities for the Presidency under "the most stressing conditions":

"Survive a nuclear attack, even one which involves repeated attacks over a long period of time."

"Direct... our strategic and theater nuclear forces..."

"Conduct... negotiations with adversaries and with our allies..."

"Control... domestic affairs during the conflict and the national recovery after..." This was revolutionary. The old doctrine envisioned nuclear war as a sudden, fatal heart attack. The new framework treated it as a prolonged, complex illness requiring sustained management.

Meanwhile, in Suriname, the U.S. moved to plug the intelligence gap. By August 1980, the White House approved a memo demanding "high quality intel from Central America and a Defense Attaché in Suriname as soon as possible." The Paramaribo embassy began a transformation: enhanced communications, expanded staff, and the arrival of personnel with deeper intelligence pedigrees.

Brzezinski hailed PD-58 as "a step of enormous strategic importance," a "major revision of our strategic doctrine, the third one since World War II." It was a decisive shift from the "1914 syndrome" of rigid, irreversible war plans toward a flexible, enduring C3I capability. PD-58 was part of a suite of directives (PD-18, PD-41, PD-53, PD-57, PD-59) transforming U.S. strategy from Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD's "spasm war") to a doctrine capable of managing protracted conflict while preserving command. Brzezinski noted prior planning "presumes a short war...no mobilization requirements...no defense!" This "Carter Transformation" addressed these perilous oversights.

But what Carter forged as a shield, his successor would retool into a sword.

From Carter's Shield to Reagan's Sword: The COG Metamorphosis

My childhood proximity to Bouterse's Suriname might seem a universe away from the high-stakes nuclear strategy sessions in Carter's White House. Yet, the Zanderij runway incident, five years before our arrival, was not merely a footnote; it was an accelerant, reshaping America's very blueprint for surviving—and potentially fighting—a nuclear war.

What many analyses of U.S. actions in Suriname overlook is this critical juncture: the profound vulnerabilities exposed by the EC-135 stranding became inextricably linked to the Carter administration's urgent overhaul of America's Continuity of Government (COG) framework. This was not just about protecting Suriname's bauxite or countering a fledgling leftist regime; it was about ensuring the United States could function, command, and control its forces through the unimaginable chaos of a nuclear exchange.

What began under Carter as an urgent, legitimate response to glaring national security weaknesses—the imperative to ensure leadership survival and operational continuity in a crisis—inadvertently forged both the template and the operational cover for something far more expansive and ultimately, more sinister. The COG framework, with its emphasis on secure, redundant communications, autonomous funding streams, and pre-delegated authorities operating outside conventional channels, created a ready-made architecture for conducting highly sensitive, deniable operations. The very principles designed to ensure presidential succession during nuclear Armageddon could, with a slight shift in intent, empower covert foreign interventions. This dual-use potential did not escape the notice of the incoming Reagan administration.

Presidential Directive 58 wasn't a solitary reform. It was the capstone of a sweeping transformation of U.S. strategic doctrine, implemented through a series of interconnected Presidential Directives under Carter:

PD-18 (August 1977): Mandated strategic force "essential equivalence" with the Soviets and called for a new rapid deployment force.

PD-41 (September 1978): Elevated civil defense to a component of the strategic balance.

PD-53 (November 1979): Ordered the creation of resilient telecommunications capabilities for a protracted nuclear conflict.

PD-57 (March 1980): Initiated the first comprehensive national mobilization planning in decades.

PD-58 (June 1980): Fundamentally reformed continuity of government planning.

PD-59 (July 1980): Revised nuclear weapons employment policy, moving towards more flexible, targeted options.

These COG reforms were deeply intertwined with an evolving U.S. nuclear strategy. The long-dominant doctrine of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) had nightmarishly envisioned a singular, massive nuclear exchange—a "spasm war" over in hours, after which the niceties of post-attack governance would be tragically moot.

But National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski forcefully argued to President Carter that America had become ensnared in a dangerous "1914 syndrome"—a reference to the rigid, irreversible war plans that had catapulted Europe into World War I. The existing U.S. nuclear war plan, the SIOP (Single Integrated Operational Plan), offered the President few options beyond all-out, catastrophic retaliation.

PD-59, by introducing more flexible nuclear targeting options, complemented the COG reforms of PD-58, which ensured that a functioning leadership would survive to implement these more nuanced responses. Together, Brzezinski championed them as a "major revision of our strategic doctrine," designed to forge both a more credible deterrent and a more viable war-management capability should deterrence catastrophically fail. As Brzezinski starkly noted in a classified assessment, previous U.S. nuclear planning "presumes a short war, a few days at most. It presumes no mobilization requirements. It even presumes no defense!" The new doctrine, born from the ashes of old illusions, confronted these terrifying oversights by preparing for a potentially protracted nuclear conflict and preserving the governmental functions essential to sustain it.

Collectively, these directives represented what Brzezinski himself termed "the Carter Transformation of Our Strategic Doctrine"—a seismic shift away from the all-or-nothing MAD paradigm toward a more adaptable, resilient posture capable of managing extended global crises while preserving the continuity of command.

But Carter's successor would take these reforms into uncharted territory.

Reagan's Gambit: COG as a Covert Launchpad

The Reagan administration inherited Carter’s COG architecture—and saw opportunity. Continuity of Government, designed to safeguard leadership, became the clandestine scaffolding for projecting power. By December 1981, Oliver North helmed the PD/NSC-58 Interagency Working Group. With Cold War hawks like FEMA's Ralph Elder and CIA's Fred Albertson, North rapidly transmuted COG planning into an engine for shadow foreign policy. Within ten months, Reagan inked three NSDDs building on PD-58, granting his team unprecedented operational latitude:

NSDD-47 (July 22, 1982): "Emergency Mobilization Preparedness" as core national policy.

NSDD-55 (September 14, 1982): Codified "Enduring National Leadership."

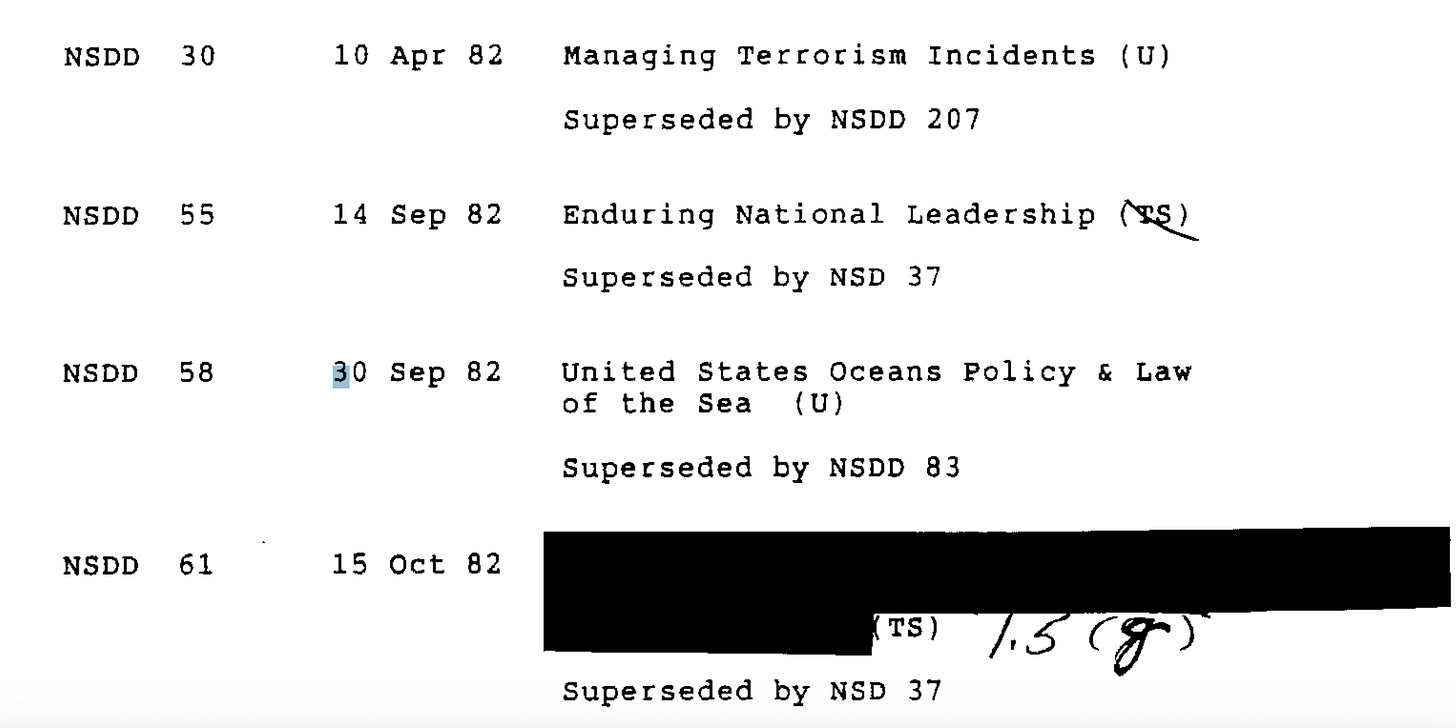

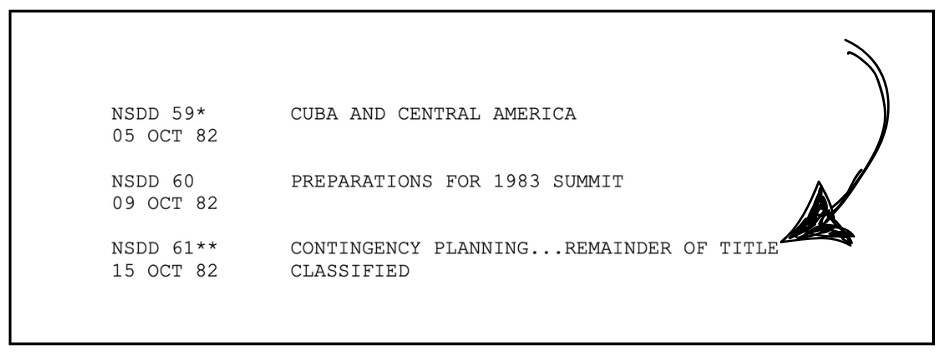

NSDD-61 (October 15, 1982): The most opaque. Ostensibly about NEACP aircraft, but potentially the keystone of a secret directive to intervene in Suriname.

The Power of Secrecy: National Security Decision Directives

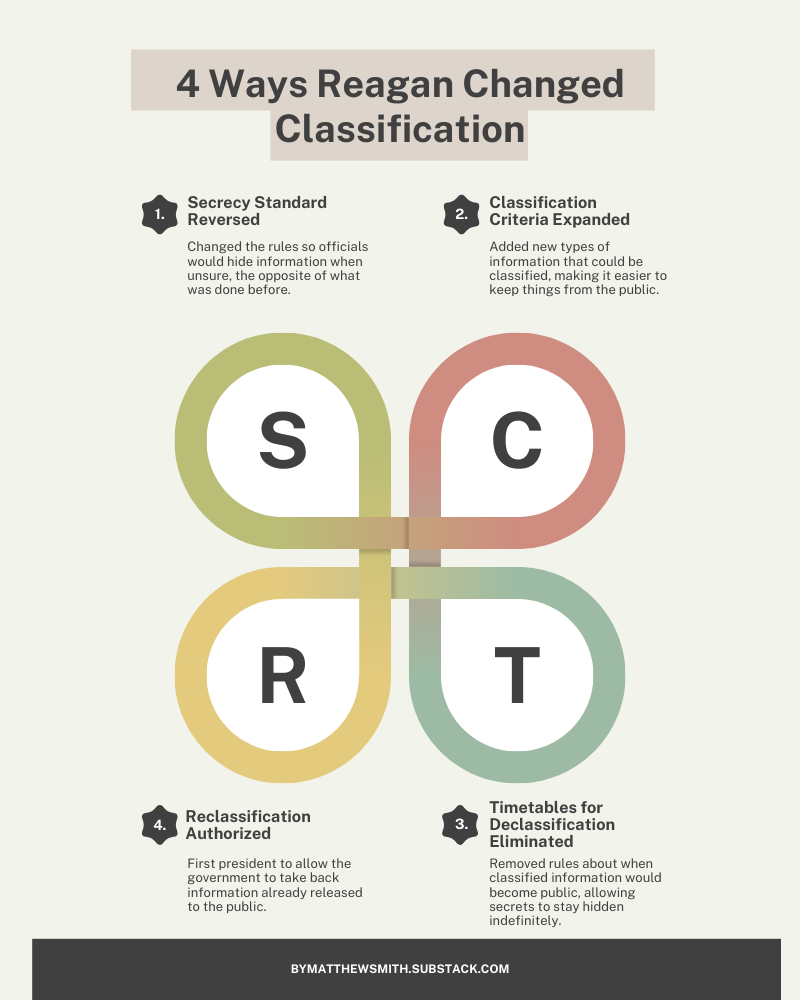

To grasp how an operation like the one brewing in Suriname could materialize, one must understand Reagan's transformation of classified presidential directives. Historically tools for guiding policy, under Reagan, NSDDs became a formidable architecture for covert action. Unlike Executive Orders (published, subject to judicial review), NSDDs are inherently secret—no public disclosure, no congressional approval, often no judicial oversight. They are classified fiats establishing policy, authorizing funds, and empowering agencies to act with minimal accountability.

Reagan wielded this power more aggressively than any predecessor: over 280 NSDDs to Carter's 63 PDs, and shrouded in far deeper secrecy. His Executive Order 12356 (April 1982) institutionalized this opacity:

Reversed declassification standards, prioritizing secrecy.

Broadened classifiable categories (e.g., vague "foreign policy").

Eliminated automatic declassification timelines.

Allowed reclassification, even after public release.

This SCRT Model (Secrecy, Classification, Reclassification, Timelines-eliminated) created the ideal ecosystem for a shadow presidency, where monumental decisions were made and executed beyond public or congressional scrutiny.

Reagan's NSDDs authorized everything from Middle East "preemptive strike" squads to "public diplomacy" that erased the line between intelligence and propaganda. Some, like NSDD-17 (arming the Contras), are infamous. Others remain buried. NSDD-61 was born into this world—a world where a presidential directive could secretly fund, staff, and coordinate the overthrow of a foreign government. What Carter began as defense, Reagan weaponized. The outcome wasn't just readiness; it was reach.

The Shadow Directive: NSDD-61's Dark Duality

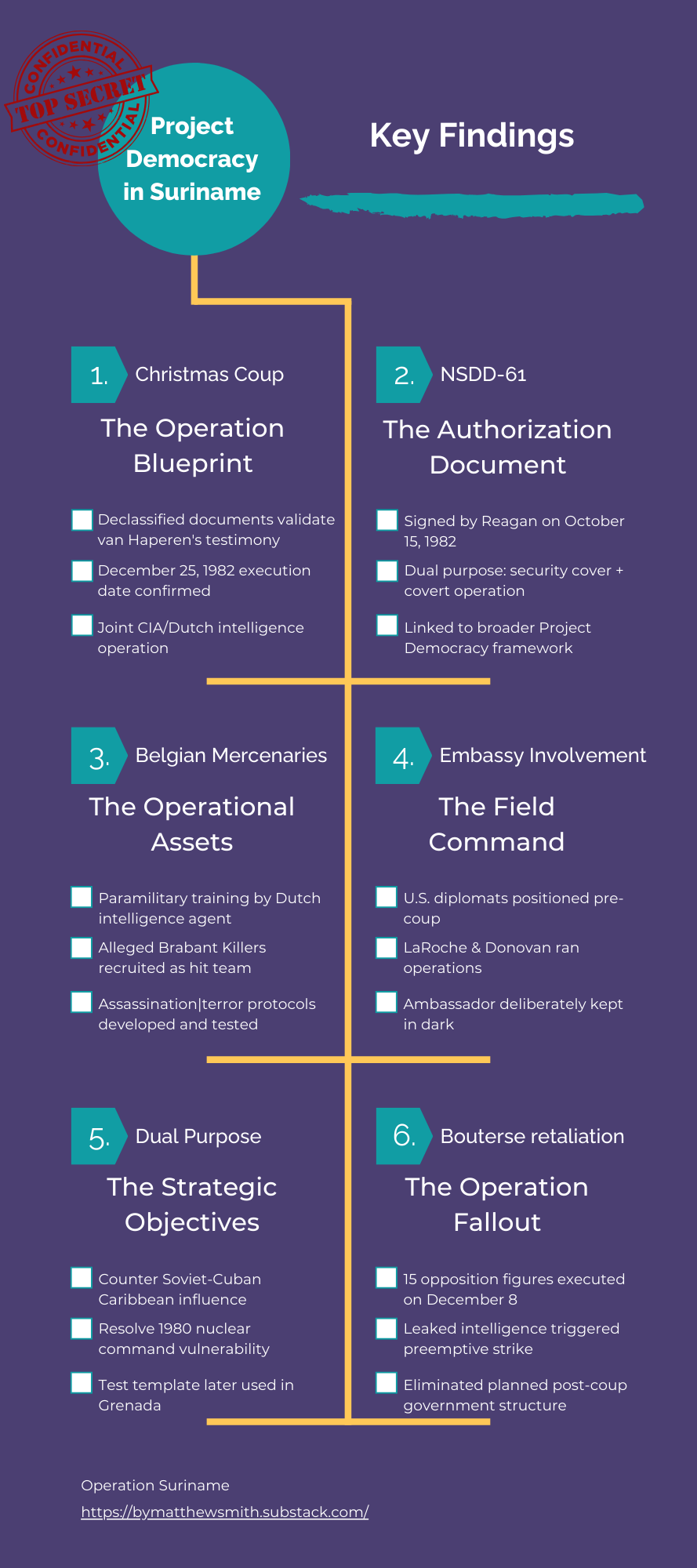

October 15, 1982. President Reagan signed National Security Decision Directive 61. It remains classified to this day. Officially, it addressed NEACP vulnerabilities. But its timing, the players involved, and the geopolitical storm clouds pointed to something far more sinister. This wasn't just a COG update; it was a launch code.

Timing: NSDD-61 preceded by weeks the December 8, 1982, "December Murders" in Suriname, where Bouterse tortured and executed fifteen critics. Bouterse’s justification: they were U.S. collaborators in what some involved called the "Red Christmas" coup. While a murderer's excuse, evidence of U.S. covert attention, CIA operatives, Gladio-linked mercenaries, and an active government-in-exile lent a chilling plausibility to a U.S.-backed plot.

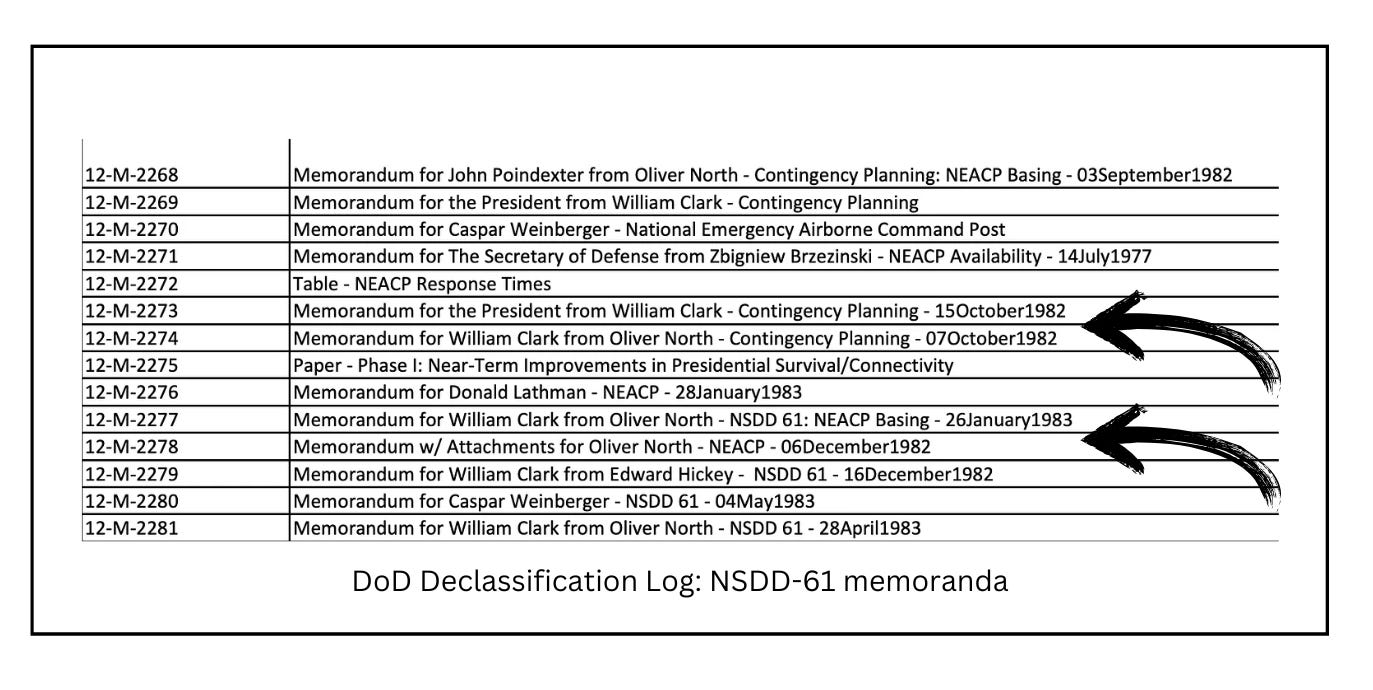

The Personnel: Reagan Library memos confirm NSDD-61’s drafting involved future Iran-Contra luminaries: Oliver North, Robert McFarlane, Constantine Menges. These were not bureaucrats; they were covert action architects. (See image: DOD Declassification Log for NSDD-61 communications). Archival logs show NSDD-61 remained active until May 1991. Unlike other directives of its era, its very title remains redacted in declassification indexes—why, if it only concerned NEACP readiness? North, already leading COG planning, was concurrently running "Red Cell" terrorism drills in Washington, exercises that, as a 1985 Soldier of Fortune article detailed, eerily prefigured the alleged Suriname plot.

The Context:

NSDD-61 was no isolate. NSDD-17 had already unleashed covert force in the Western Hemisphere. NSDDs 47 and 55 had laid COG’s logistical groundwork. NSDD-61 fused them, redirecting readiness infrastructure towards active intervention. Its 1.5(g) classification category (intelligence activities, special operations, sensitive methods) confirms it was far more than a civil defense plan.

The Secrecy:

NSDD-61’s enduring classification is telling. Other NEACP directives are declassified. PD/NSC-58 is public. Why is NSDD-61 still locked down? The NSA's 2025 "Glomar" response (neither confirming nor denying records) to my FOIA request for U.S. Suriname operations (1981-1983) further signals deep sensitivity.

The inescapable conclusion: NSDD-61 likely contained operational mandates, using NEACP planning as a sophisticated disguise for authorizing foreign regime change. In Reagan's Washington, COG was becoming an invisible scaffold for a hidden state, capable of defensive resilience and offensive clandestine projection.

The Flashpoint: Cuba's Caribbean Gambit

While NSDD-61 likely provided formal authorization, events in Suriname had been ringing alarm bells in Washington for over a year. Bouterse’s post-coup consolidation—executions, censorship, a sharp pivot to Cuba—catapulted Suriname onto the Cold War’s front lines. The Carter White House, already shaken by the EC-135 affair, greenlit a request by August 1980 for "high quality intel from Central America and a Defense Attaché in Suriname." The U.S. Embassy in Paramaribo, then the smallest in South America with no CIA station, began a rapid buildup: upgraded communications, expanded staff, new personnel with serious intelligence backgrounds. The Army’s deniable Intelligence Support Activity (ISA) formed in April 1980, offered off-the-books operational capabilities.

Internal rifts in Suriname's Military Council saw a leftist faction under Sergeant Badrissein Sital align with Cuba and Nicaragua; Sital even met Castro in Managua in July 1980. Though Bouterse arrested him, the leftward current was strong. After Sergeant Wilfred Hawker’s failed counter-coup in March 1981 ended in his swift execution, Bouterse issued a formal socialist manifesto in May. According to Dutch intelligence agent Peter van Haperen—(whose claims increasingly resonate with declassified evidence), Bouterse and key advisor Harvey Naarendorp then made a clandestine trip to Cuba. By June, Havana had an official mission in Paramaribo. Washington was officially alarmed.

The U.S. Counter-Offensive: Setting the Stage

The American response was swift and multi-layered:

Operative Deployment: Richard LaRoche, a veteran of covert coordination in Grenada and Chile, attended Deputy Chief of Mission training (Aug-Sep 1981).

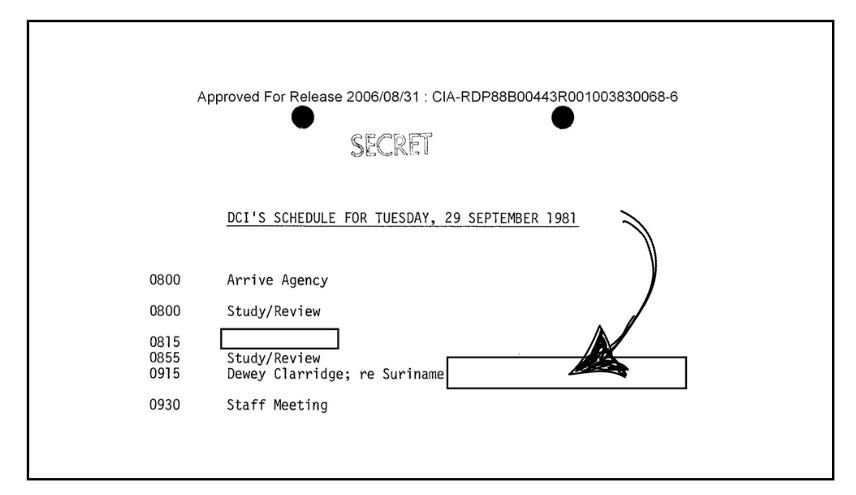

CIA High Command Focus: On September 29, 1981, Dewey Clarridge—CIA Latin America chief, later an Iran-Contra central figure—personally briefed the Director of Central Intelligence specifically on Suriname. This nation was now a top-tier U.S. strategic concern. (See image: DCI schedule with Clarridge briefing).

Opposition Mobilization: Surinamese exiles organized in the Netherlands. Van Haperen claims active coup planning began that May: “From May [1981], I was instructed to actively prepare for a potential takeover... the plan was to potentially use Dutch, Belgian, French, and possibly mercenaries.”

Formalizing Hostile Ties: The Suriname-Cuba diplomat exchange agreement (November 16, 1981), naming Cuban intelligence specialist Osvaldo Cárdenas as ambassador, concretized U.S. fears.

Internal Turmoil Escalates: February 1982: Bouterse ousted President Chin A Sen over Cuban ties. March 1982: Lt. Soerendra Rambocus’s coup attempt failed.

By mid-1982, the situation was explosive. Weapons were allegedly flowing via Van Haperen's networks from NATO depot thefts. Coup training was reportedly offered by infamous French mercenary Bob Denard. CIA-cultivated resistance groups were active. As NSDD-61 was being finalized, the Soviet Union dispatched Igor Bubnov—a former CPSU heavyweight from Washington—as its first ambassador to Paramaribo. Soon after, Grenadian PM Maurice Bishop, a key Cuban ally, visited.

Project Democracy: The Suriname Proving Ground

NSDD-17 (January 4, 1982), born from that November 1981 NSC meeting just days after the Suriname-Cuba pact, had already laid the strategic groundwork:

Military training for "indigenous units and leaders."

A "public information task force" for perception management.

Military contingency plans against "Cuban forces." It mandated support for "democratic forces"—in Suriname, this meant funding, arming, and coordinating anti-Bouterse elements, including a government-in-exile. An expansive covert architecture was erected: resistance networks like “De Stichting Herstel Democratie en Suriname” were fostered, intelligence operatives embedded in the U.S. Embassy (many pre-ambassador), assets cultivated within Bouterse’s regime, and mercenary teams recruited.

The endgame: a multi-pronged operation allegedly timed for Christmas Eve 1982—the "Red Christmas" plot. When Bouterse got wind of it, he struck first. His December 8th executions of fifteen opponents—lawyers, journalists, union leaders—were, he claimed, a preemptive strike against an imminent CIA coup.

Suriname was irrevocably scarred. The December Murders became an international outrage, crushing the democratic opposition, yet paradoxically affording the U.S. plausible deniability. The "Red Christmas" operation, though ostensibly failed, perversely demonstrated the ruthless calculus of Project Democracy: even a collapsed plan could yield strategic dividends in disruption and intimidation.

The Zanderij incident was more than a footnote. It was the inflection point where defensive COG planning was warped into an offensive covert capability. What began with stranded "Snoopy-nosed" aircraft on a remote tropical runway culminated in a blueprint for shadow warfare, tested in Paramaribo, that would be lethally refined and replicated throughout the Reagan years. Project Democracy found its first proving ground, and its first tragic victims, in the hothouse of Suriname.

As we'll explore in Part II: The Wolves of Paramaribo & Reagan's "Other" Contras, the blueprint drafted in those early, chaotic days would soon be implemented by a dedicated team of covert operatives, with devastating consequences.

Addendum:

FOIA Case 120704: The Shadow Refuses to LiftIn April 2025, I filed a FOIA request with the National Security Agency seeking documents related to U.S. operations in Suriname between August 1981 and July 1983—the precise window during which preparations for the rumored “Red Christmas” coup were allegedly underway.

The NSA’s reply was telling—not because of what it disclosed, but because of what it refused to admit. The agency invoked both Executive Order 13526 and multiple statutory protections (including 50 U.S.C. § 3024(i) and § 3605), asserting that even acknowledging the existence of such records “would be harmful” to national security.

This kind of Glomar response—neither confirming nor denying the existence of records—is the bureaucratic equivalent of blackout curtains. It typically only applies when something sensitive is at stake: covert operations, intelligence methods, or unacknowledged programs.

For comparison: if the request were frivolous or unrelated to real activities, the agency could simply reply, “We found no records.” The fact that they didn’t says everything.

Brief Glossary:

Key Terms:

C3I - Command, Control, Communications, and Intelligence: The systems that allow military and government leaders to assess situations, make decisions, and implement them during crises.

COG - Continuity of Government: Plans and procedures to ensure government functions continue during and after catastrophic events like nuclear war.

EC-135 - A modified Boeing aircraft used for various military communications and command functions.

JCS - Joint Chiefs of Staff: The group of senior military officers who advise the President and Secretary of Defense.

NEACP - National Emergency Airborne Command Post: The "Doomsday Plane" designed to keep the President and key leaders airborne during a nuclear attack.

NSDD - National Security Decision Directive: Classified presidential orders that establish national security policy.

PD - Presidential Directive: Policy documents issued by the President (used during the Carter administration).

SIOP - Single Integrated Operational Plan: The United States' master plan for nuclear war from 1961 to 2003.

see: Garrett M. Graff’s book, “Raven Rock: "The Story of the U.S. Government’s Secret Plan to Save Itself--While the Rest of Us Die.